Every facet of the Arctic, from sea ice to permafrost, from fisheries to shorelines, is responding to the effects of climate change, which is increasing temperatures of the land, air, and ocean. These changes do not occur in isolation, but are triggering impacts in different, but connected, branches of the Arctic ecosystem, like an intricate pattern of toppling dominoes. Local and Indigenous knowledge holders in the Arctic have long employed a holistic, interdisciplinary approach for understanding their environment, and the scientific research community has begun to embrace a similar framework to study interconnected changes across the Arctic environment. The NOAA Arctic Ecosystem & Climate cruise exemplifies such an approach for understanding this evolving marine ecosystem. By bringing together four unique, yet complementary, research teams encompassing an array of expertise, including students and a community observer, this cruise models how Arctic science is elevated and strengthened through inclusion.

A community visit years in the making

Big Diomede (Russia) can be seen in the background.

Credit: Seth Danielson.

After nearly three weeks at sea, 30 researchers and crew members disembarked R/V Sikuliaq onto a small island in the middle of the Bering Strait. Though only 2.5 square miles, Little Diomede Island is surrounded by life. It is just north of a biological “hot spot”, an area with an abundance of marine life that is undergoing rapid climate-induced transformation. Decreased sea-ice cover and increased water temperatures in the Bering Strait are impacting abundance and distribution of marine organisms across the food web, from plankton to pollock to whales. Researchers with the Distributed Biological Observatory (DBO) project have been sampling ocean water and seafloor sediments annually in the region since the 1980s, monitoring this transformation as it unfolds to better understand ecosystem sensitivities. Ecosystem changes have direct and profound effects on the residents of Little Diomede Island who rely on healthy fish and marine mammals as key components of a traditional diet.

“The ocean provides food for us, and for the world,” says Opik Ahkinga, who joined Sikuliaq for the third time as a community observer. Opik calls Little Diomede Island home, and her love for the ocean was instilled in her from an early age by her father, who now at the age of 88 is the eldest Diomede member. Since Opik’s first time on Sikuliaq as a community observer with the Chukchi Ecosystem Observatory (CEO) project in 2017, she and University of Alaska Fairbanks professor and CEO chief scientist Seth Danielson have built and maintained a relationship based on friendship, respect, and mutual learning. “Opik dives into helping the science teams complete their sampling and is both a fountain and a sponge of information,” says Seth. “The scientists are always keen to hear her stories of life in Bering Strait, which provide a direct window into the culture and people who live here.”

The Little Diomede community is interested in what the researchers are learning about the Bering Strait region, and how western science can supplement their own knowledge systems to inform their traditional and customary hunting and fishing practices. Similarly, weaving Indigenous knowledge and community concerns into science planning ensures that the research outcomes are relevant and useful for those most affected by a changing Arctic.

This year, the Sikuliaq science party was invited, for the first time, to visit with the residents of Little Diomede Island, a reflection of the sense of trust that has been built over years of sustained communication and collaboration.

Credit: Shaun Bell

During this visit, there was a true exchange between the groups: after a formal welcome from Diomede Mayor Robert Soolook Jr., the research team presented short talks to the community, describing cruise objectives, methods, and observations from ocean physics and marine mammals to environmental DNA and Arctic zooplankton. Inaliq tribal members then shared traditional drumming and dance, eventually inviting the science party to join in. Danielson provided Mayor Soolook Jr. and others from the community a tour of the Sikuliaq before ending the evening by sharing a meal onboard the ship.

Opik said that she wanted the research team to see Little Diomede and meet the people who live there, as a way to connect the impacts of a changing marine ecosystem to the people whose cultural values are challenged by those impacts.

“We don’t have the strong old ice anymore… this young ice, we must learn to adapt to understand. Our Inaliq knowledge of hunting walrus, seals, and crabbing on ice will be gone… it is already happening.”

– Opik Ahinga, community observer and Diomede resident

Inclusion affects who feels like they belong in Arctic research (and who ends up staying)

An inclusive approach is beneficial not only between scientists and the communities in which they work, but also within the research community itself. Dr. Christina Goethel, a benthic ecologist who celebrated her 20th expedition on this year’s cruise, is a shining example of the power of inclusion in research. Christina can trace her DBO legacy back a full decade to her master’s degree project, when her training in Arctic marine science began. Excitement about the work and the positive mentorship from her advisors evolved into a PhD with DBO, and she continues working closely with the cruise planning team (including Drs. Jackie Grebmeier and Lee Cooper, DBO principal investigators and Christina’s graduate work advisors) to steer research objectives and cruise coordination.

sediment samples to be shipped back to their lab in Maryland.

Credit: Seth Danielson.

While her curiosity for how seafloor organisms, primarily bivalves like clams, respond to environmental stressors of warming ocean waters continues to drive her work, the reason she has stayed with DBO for so long is simple: “I’ve always been drawn to the willingness of the program to bring in people with different perspectives,” Christina says, highlighting that she’s sailed with artists, photographers, and authors over the years who have been invited to help tell the story of Arctic research.

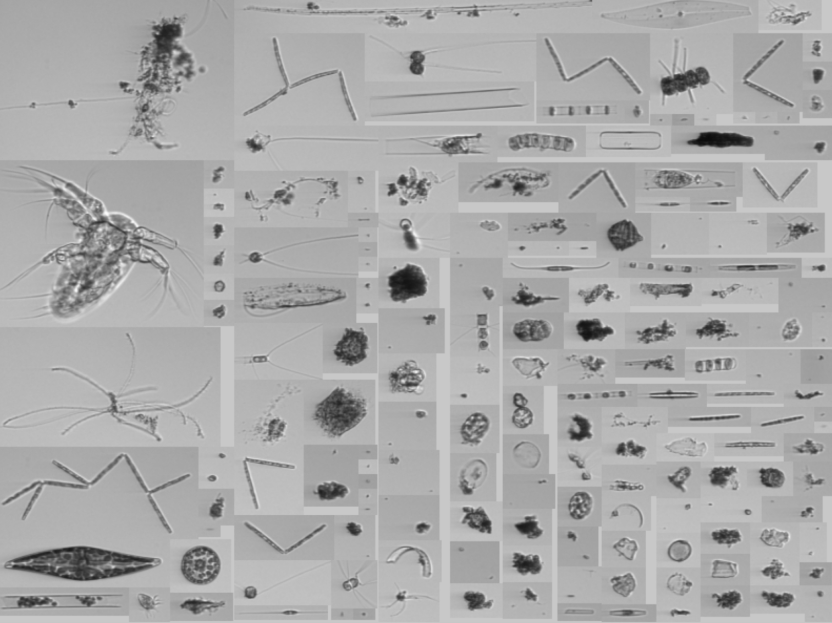

She describes the culture of the DBO program as human-first: while the research seeks to answer fundamental ecological and environmental questions, the “why” is focused on translating the science into useful information for Arctic communities. The emergence of harmful algal blooms (HABs) in the Arctic, for example, is a new, unfamiliar threat to human health driven by warming ocean waters in the region. While underway, scientists from each of the four research projects constantly examine water samples for evidence of specific HABs algae, and if observed they have a protocol in place to rapidly and widely alert nearby communities.

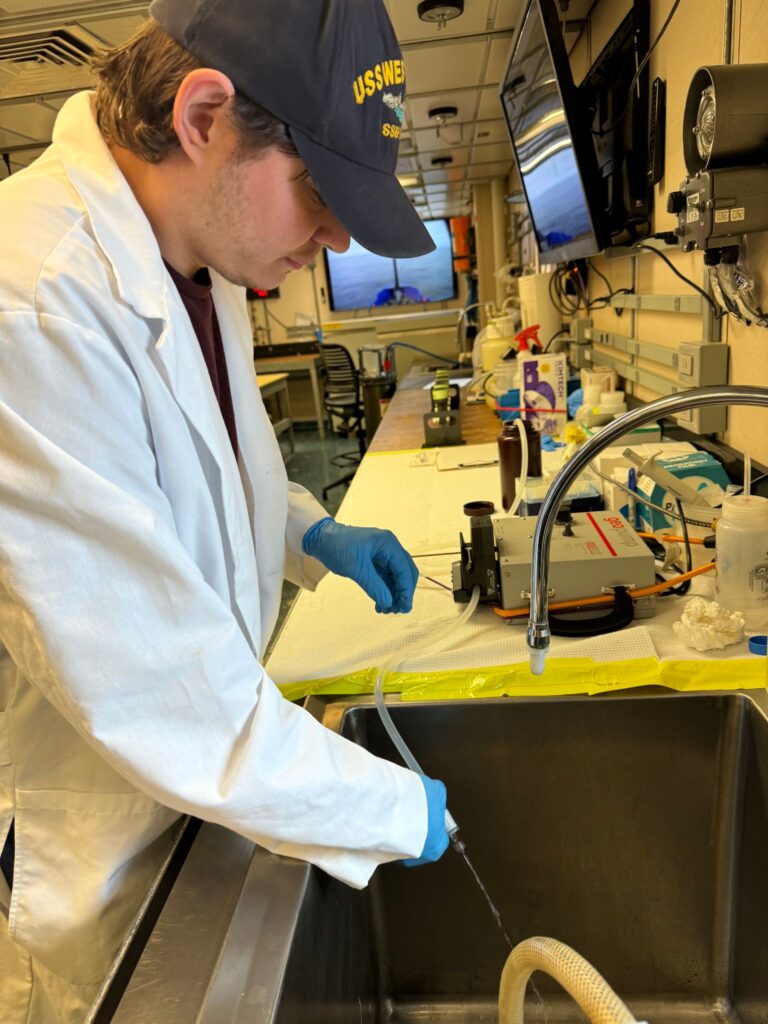

microscope camera. These phytoplankton photographs help researchers look out for

harmful algal bloom species. Credit: Evie Fachon.

This emphasis on connecting science to people extends to the culture of the research team, which according to Christina, ultimately “leads to better science and more efficient collaboration – that’s especially important when you’re working on a platform that costs $65,000 a day to operate!”

The culture of inclusion continues to be passed down through the DBO generations: Christina brought Robert Koontz, an undergraduate student at St. Mary’s College in Maryland, to join the research team aboard the Sikuliaq as part of a summer internship. Although it was his first research cruise, after 12 years in the Navy, Robert was no stranger to life at sea. He worried he might feel like a fish out of water surrounded by subject matter experts, but Robert said that Christina’s mentoring style quickly helped him to feel at ease and like one of the team. “Dr. Goethel has many interdisciplinary connections that led to me being able to not just work with her benthic team, but also the physical oceanography team as well,” Robert said. “She did a great job at introducing me to these other scientific teams and then allowed me to build my own connections, which helped me to build my own sense of belonging on the cruise.”

board the R/V Sikuliaq. Credit: Katrin Iken.

“[Dr. Goethel] did a great job at introducing me to these other scientific teams and then allowed me to build my own connections, which helped me to build my own sense of belonging on the cruise.”

– Robert Koontz, undergraduate researcher with DBO

Empowered by this sense of belonging, Robert embraced opportunities to work alongside scientists from other research initiatives on board, including EcoFOCI (Ecosystems & Fisheries-Oceanography Coordinated Investigations) and AMBON (Arctic Marine Biodiversity Observing Network) and to learn new skills (like filtering water samples for environmental DNA!) along the way.

Looking forward, together

The ongoing transitions in the Arctic are unprecedented, and Alaskan communities are already having to adapt to these changes. Residents of Little Diomede hold extensive, intimate knowledge of their environment – the same environment that the Sikuliaq team is passionate about understanding. Embracing inclusion of multiple perspectives, paradigms, ways of knowing, and people enhances our ability to understand these changes and, importantly, develop tools and resources that strengthen community resilience. This year’s shore visit and Opik’s and Robert’s integration into the research team are examples of respect for different ways of knowing, and of how collaboration can enrich our understanding of Arctic change across all communities.

The NOAA Arctic Ecosystem & Climate cruise is a joint project funded by the GOMO Arctic Research Program and NOAA Fisheries, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the North Pacific Research Board, the Alaska Ocean Observing System, the U.S. Office of Naval Research, and the University of Alaska Fairbanks.