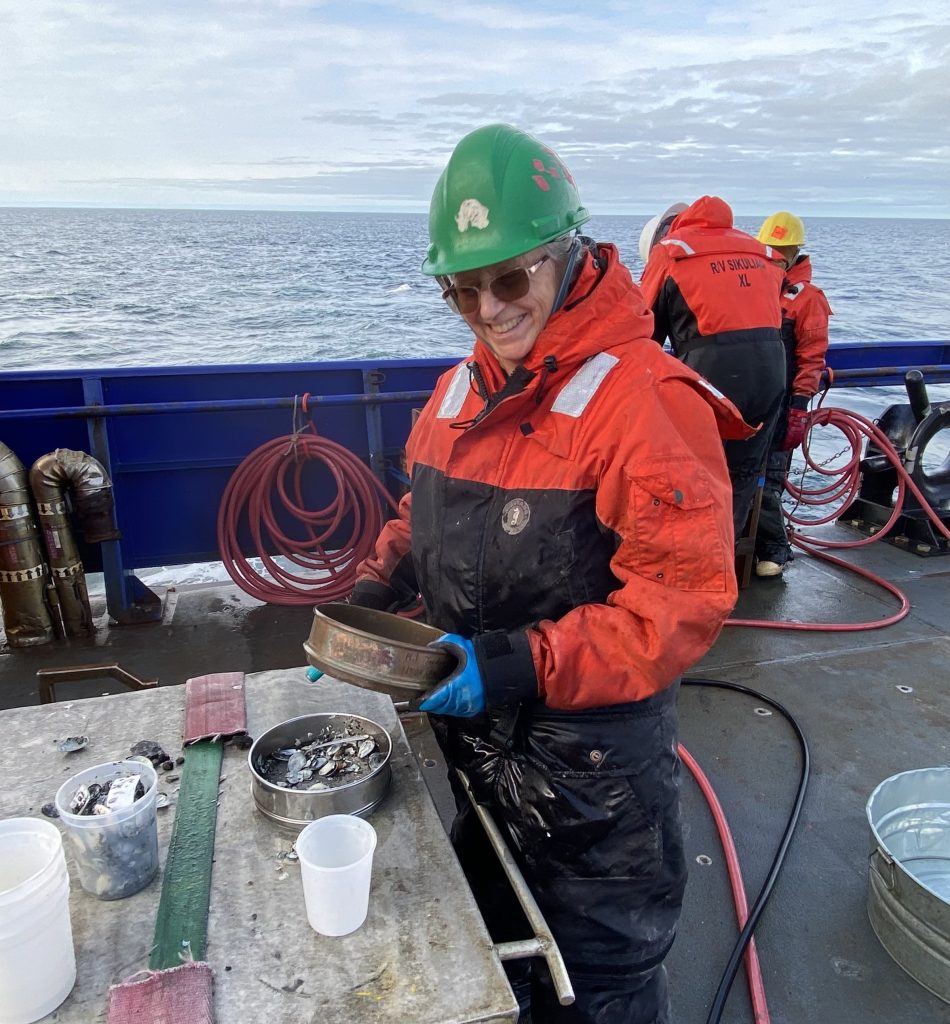

In the middle of the cold and wavy Bering Sea, a crane extends over the stern of the R/V Sikuliaq and brings aboard a metal scoop filled with a sample collected from the muddy bottom of the seafloor. Researchers, Jackie, Lee, and colleagues, sort through the mud samples to catalog the hundreds of organisms it contains – clams, worms, amphipods, and brittle stars. Some of the critters will go on to be used in experimental studies on how climate change is affecting metabolism, others will be preserved for genetic and taxonomic analyses, and others will be sampled for concentrations of harmful algal toxins to ensure the safety of shellfish consumption in the area. The remaining scientists on the ship are busy identifying and counting zooplankton, some are filtering water for measures of phytoplankton, and some are keeping track of marine mammal sightings. This is the busy but steady hum of scientific observations aboard a research vessel.

For the past 40 years, Jacqueline “Jackie” Grebmeier and Lee Cooper have spent months in a variety of locations within the Arctic aboard 100+ foot research ships. Grebmeier and Cooper, both professors at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (UMCES), have dedicated their scientific careers to characterizing and communicating the impacts a warmer Arctic is having on marine ecosystems. Currently, the Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the rest of the planet, resulting in sea ice loss, a warmer ocean, and marine food webs that are changing dramatically.

However, Grebmeier and Cooper are not just contributing to the research, they are connecting and building scientific communities focused on improving our understanding of Arctic marine ecosystems. They are two of the scientific leads of the Distributed Biological Observatory, a program aimed at developing a framework for collecting and analyzing data that examines the diversity, distribution, and drivers of marine life in the Arctic over time and space. Stations in biological hotspots of the Bering and Chukchi Seas were chosen to catalog the diversity of life present, the key drivers from the ecosystem, and how the system is changing with the ongoing impacts of climate change. Detecting and understanding these changes requires extensive analysis of observations taken from the ocean’s surface to the seafloor, as well as data collected from controlled experiments.

The Distributed Biological Observatory (DBO) has been a catalyst for national and international collaboration, technology development, and new understanding of how Arctic marine food webs are changing. Since its formal development in 2010, the DBO has served as a model of scientific research and has been replicated across the Arctic. Partnerships have been formed with scientists in China, Japan, Korea, Canada, and Russia, and with the expansion to a Pan-Arctic DBO network, collaboration with many European Union countries.

Within the US, Cooper and Grebmeier have also collaborated closely with academic and federal partners. For example, this past September, NOAA’s Arctic Marine Ecosystems Cruise was split among four major projects contributing to a better understanding of how the Arctic is changing: the Distributed Biological Observatory (DBO), Ecosystem & Fisheries-Oceanography Coordinated Investigations (EcoFOCI), the Arctic Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (AMBON), and the Chukchi Ecosystem Observatory (CEO). During the cruise, Principal Investigators Jackie Grebmeier (DBO, UMCES), Katrin Iken (AMBON, University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF)), Phyllis Stabeno (EcoFOCI, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory), and Seth Danielson (CEO, UAF) worked together to coordinate the 24-person science party and the varying but complementary scientific interests of each program. Together, the combined efforts of these programs took full advantage of the time at sea to collect a wide range of biological and environmental data on everything from physical and chemical oceanography to biodiversity of water column plankton to communities living in the muddy floor of the ocean as well as seabirds and marine mammals.

Large collaborative research cruises require extensive communication and teamwork, but are not new to seasoned Arctic scientists like Grebeimer and Cooper. Logistically, field-work in the Arctic is often challenging and expensive and thus collaborative research expeditions and projects are critical to advancing the number and quality of observations in the Arctic. In recent years, NOAA funding for the DBO has supported time on specialized ships, like R/V Sikuliaq and USCGC Healy, which are ice capable, and have the ability to recover and deploy large moored instruments that provide year-long coverage of conditions in the northern Bering and Chukchi seas. These ships are also equipped with controlled laboratory spaces that simulate seafloor ocean temperatures and allow scientists to conduct experiments at sea on samples collected in Arctic waters. With these specialized laboratories, scientists can track in real-time how ocean life responds to and performs under different ocean conditions.

It is hard to over-emphasize the importance and utility of the comprehensive and long-term dataset that DBO provides through national and international collaborations. Understanding how Arctic food webs are changing is vital to the management and conservation of important marine resources. Local and Indigenous communities rely on healthy marine food webs for subsistence hunting and fishing activities that fulfill nutritional and cultural needs. Globally, and particularly as fisheries move northward, Arctic marine ecosystems support significant fisheries industry and international economic activities.

In addition to collaborating broadly with the scientific community, Grebmeir and Cooper are committed to sharing and exchanging knowledge with local communities in Alaska. After almost every research cruise within Alaska, they organize an event to share their findings with local students and interested groups. This past September, for example, Grebmeir and Cooper along with other scientists aboard the NOAA Arctic Marine Ecosystems Cruise made presentations to three classes at the Anvil Science Academy magnet school in Nome and gave a public talk as part of the Strait Science Lecture Series provided by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Northwest Campus and Alaska Sea Grant. There is a wide range of interest from local communities in Alaska to learn about, consult on, benefit from, and/or contribute to scientific activities nearby.

Cooper reflects “it is in scientists’ best interests to be sensitive to the needs of local communities and communicate with local groups to avoid disturbing any hunting or fishing activities.” He also stresses that another important area for researchers to get involved with communities is “to assist projects that help test and monitor for harmful algal blooms that impact human health since many small communities in Alaska are heavily dependent upon local food gathering activities.”

When they are not at sea, in the classroom, or in the laboratory, Grebmeier and Cooper are often writing scientific publications – they contributed to the latest Arctic Report Card – and sharing data and observations at scientific conferences and intergovernmental meetings. This year, their research will take them to New Orleans for the Ocean Sciences Meeting and Edinburgh for the Arctic Science Summit Week where they will compare information with scientists from around the circumpolar Arctic and work with others to address the scientific needs for observing Arctic change. They will also prepare for the next field season of data collection with cruises to both the Bering and Chukchi seas. For these ever-curious and dedicated scientists, every day at sea is a new opportunity and any time in the dramatically changing Arctic is a gift.