This is a repost of a NOAA Research article published December 5, 2023. Read the original post here.

NOAA data and models help scientists track the global carbon cycle

Greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels are projected to reach a record 36.8 billion metric tons in 2023, an increase of 1.1% over 2022, according to an annual report by the Global Carbon Project.

While emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) are declining in some regions including Europe and the United States, they continue to rise overall, the authors said, adding that global action to reduce fossil fuel consumption is not happening fast enough to prevent dangerous impacts from climate change.

The steep reductions that are urgently needed to meet global climate targets have yet to emerge, said Professor Pierre Friedlingstein of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute, who led the study. Atmospheric CO2 in 2023 will likely reach 419.2 ppm, 51% above pre-industrial levels.

“The impacts of climate change are evident all around us, but action to reduce carbon emissions from fossil fuels remains painfully slow,” Friedlingstein said.

At current rates of emissions, the scientists calculate there is a 50% chance that within seven years global temperatures will regularly exceed the 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels identified in the 2015 Paris Agreement as a threshold beyond which worsening and potentially irreversible effects of global warming are likely to emerge.

Reaching net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 would require cutting total emissions by roughly the same amount observed during the coronavirus slowdown – 1.8 billion tonnes – year after year, the report said. Given the long lifetime of CO2 in the atmosphere, the temperature level already observed will persist for several decades even if emissions are rapidly reduced to net zero.

The findings were announced today at COP28, the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

NOAA’s observing networks are key

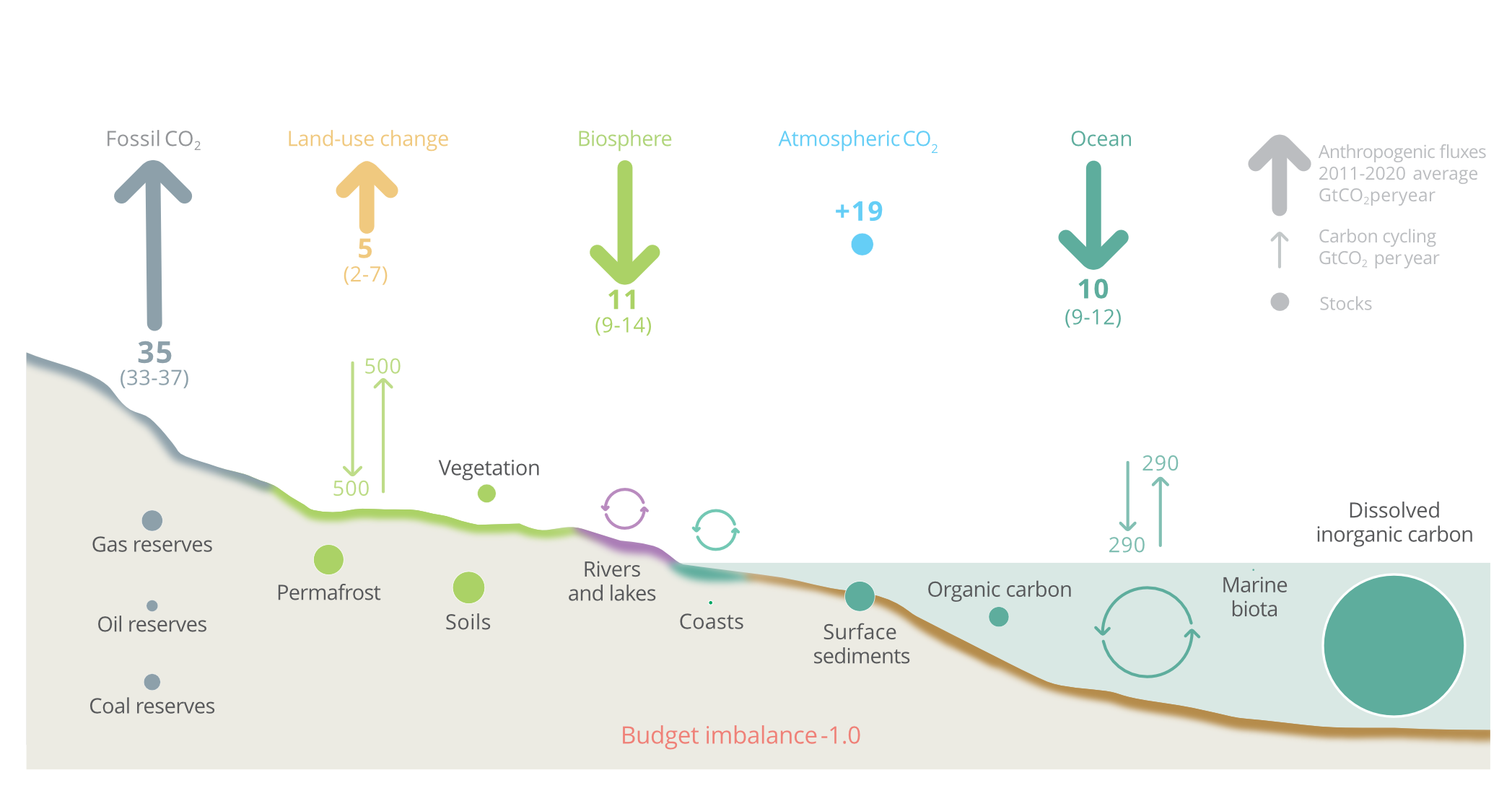

Ninety scientific institutions around the world contribute to the Global Carbon Budget report, released annually since 2003. It estimates how much carbon is emitted each year from human activities and how much is absorbed by carbon sinks such as terrestrial plants, soils, and the ocean. Roughly 25% is absorbed by the ocean and just under 30% by land ecosystems, with the rest remaining in the atmosphere for hundreds or thousands of years.

The Global Carbon Budget relies on data from NOAA’s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network as a primary source for estimating emissions and atmospheric CO2 levels. NOAA provides about a quarter of all the atmospheric CO2 observations used in the analysis. This year, for the first time, NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory’s CarbonTracker global model of atmospheric CO2 was used to help estimate global sources and sinks.

“The global extent of our atmosphere and ocean sampling network provides an invaluable foundation for understanding the carbon budget,” said Colm Sweeney, associate director for science at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory.

NOAA also provides roughly half of all the surface ocean CO2 observations, collected from hundreds of sensors on ships, buoys, moorings and autonomous surface vehicles sponsored by NOAA’s Global Ocean Monitoring and Observing program, which are included in a global database used to calculate the ocean carbon sink.

These baseline measurements are essential for understanding the global carbon cycle, including the amount of carbon emitted to the atmosphere and the amount removed by carbon sinks such as terrestrial plants, soils and the ocean.

Fossil fuel emissions and land use changes

Global emissions from coal, oil and gas, the main driver of rising atmospheric CO2 levels, are all projected to increase in 2023, the report said. Eighteen countries representing about 20% of world fossil CO2 emissions saw their emissions decrease during the 10 years from 2013 to 2022, but those gains have been offset by increasing emissions elsewhere.

Changes in land-use management also generate carbon emissions. The report said emissions from global land-use changes and deforestation in 2023 were projected to reach 4 billion metric tons of CO2, down from 4.7 billion metric tons per year from 2013–2022. Forests sequester, only enough to offset two-thirds of the carbon released by deforestation.

Questions about the ocean sink

One emerging question is whether the ocean will continue to absorb CO2 at current rates. A NOAA-led study published this year that analyzed global ocean carbon storage over two decades, indicates the ocean carbon sink may be weakening.

The reason for this weakening may be two-fold, the authors said. Roughly half of the slowed rate of absorption could be because the ocean has reached a point at which it has accumulated substantial amounts of CO2 and is now beginning to take up less additional CO2. A second cause may be due to changes in global ocean circulation leading to decreased transport of carbon from surface waters to the ocean interior, where it can be stored on the timescale of centuries.

“As we work towards achieving net zero emissions, we have been expecting natural sinks to behave the way they have in the past,” explained Rik Wanninkhof, senior scientist at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory who leads the Ocean Carbon Cycle Group. “If they don’t, we’ll have to decrease emissions even more than expected.”

Looking to the future, there are several areas of research that could help improve scientific understanding of the carbon cycle, said NOAA scientists who contributed to the study. They include reducing a persistent large uncertainty in the estimate of emissions from land-use change, reducing disagreement between methods that estimate sources and sinks from northern hemisphere lands, and resolving a discrepancy between the different methods for estimating the strength of the ocean sink over the last decade.

To read the full Global Carbon Budget report, see: https://globalcarbonbudget.org/carbonbudget2023/

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications, at (303) 819-7409 or theo.stein@noaa.gov.